Between Places: art, architecture and public space

Richard Dunn

Abstract

Architecture and planning as material practices create private and public space and place. The significance of this for everyday life – personal and social relations – is often overlooked as commercial, political and social interests contest the same ground. Given the interpenetration of interests, there is the potential for disciplines outside those of architecture and planning, to critically respond to or expand possibilities for understanding and producing public urban space. This paper will consider public urban space as a site for public action and explore the concepts of betweenness that impact on public space. At a human level, such spaces may call for a greater kinesthetic than aesthetic response, involving mental constructs and images. An understanding of public space and place as a ‘situation’ is proposed in which the possibility for action is extended and the public is identified as a social and democratic ‘field’.

‘On the pretext of rationalizing city planning, modern architects and city planners have produced a mythical architecture par excellence: the labyrinth that is the city today. In this context, art can be a source of regeneration whose objective is not so much to depict a collective dream as to liberate us from it.’

– Collective La ciutat de la gent

Introduction: buildings and places

The purpose of this paper is be to discuss the limits of public space and its public use, speculating upon it in a somewhat Kantian sense rather than to describe particular case studies, or propose idealised models or generalised solutions.

I will discuss the implications of some theoretical terms that have been used to describe and form the idea of public space. And I will focus on the spatial concept of ‘between’ which is used in architectural theories of deconstruction and modernist legacy.

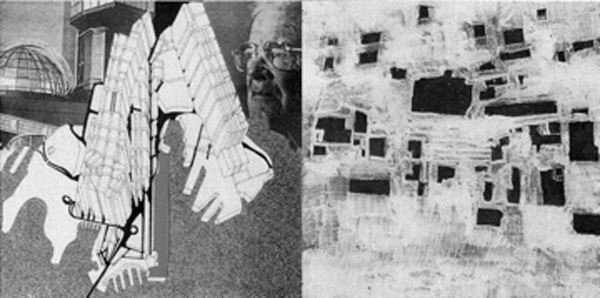

The insights that prompted this speculation developed from two experiences where art and architecture have been in close alignment. The first, with the architect Graham Jahn, was to look at the CBD of Sydney in detail, on foot and by car, building by building. Together, we realised that there will be multiple possibilities to reconfigure the city, including its street pattern and public places, over, say, a fifty-year time span. However, given the nature of property ownership and development, this idea, although sensible for a city like Sydney, is not practicable. Nevertheless the work, ‘Fractal City’, which was made for the artist/architect exhibition Future City (1992) identified sections of Sydney available in a long-term plan and raised fundamental questions about city development orientated toward the city’s users. ()

fig.1 Graham Jahn & Richard Dunn. Fractal City, detail, 1992 (© author)

The second experience was a four-year project in Chemnitz, Germany, imaging the city after it’s bombing the day after Dresden in 1945; development in the GDR, and after reunification in 1990. In Chemnitz I carried out an informal audit – a kind of ‘urban archaeology’, which, in retrospect was not unlike Walter Benjamin’s method in Paris. Like the Sydney study, this work in Chemnitz was carried out on foot and by car, in the manner of Benjamin’s ‘flaneur’ with a growing understanding informed by the material facts of the city itself, rather than texts. The mapped location of buildings of interest formed a matrix, a network across the whole city. The outcome of the work in Chemnitz, Blickdicht, was a museum exhibition of montaged building and textile photographs, showing their architectonic, social and technical conditions and included historical textile products – women’s stockings made between 1895-1910. (fig.2) This exhibition changed the perception of Chemnitzers to their city.

fig.2 Richard Dunn, Congress Hall and Hotel, 1974, Rudolph Weisser, 2004 colour photo 30x81cm (© author)

These two experiences made obvious the aesthetic affect of buildings in the built order in forming memories and identity: that by its material definition and overt visuality all space is public. Artist Robert Morris articulated such a relationship between objects and the viewer as involving “kinesthetic clues, memory traces, and physiological factors….”

From a regulatory position the border between public and private space is clearly established by site boundaries – private space is property and planning controls represent public interest. However, the border between public and private space is, even at the level of function, more permeable than ownership, financial interest and regulatory requirement allow.

UNSW law professor George Williams is quoted in a July 2006 Sunday Age article addressing the question of public-use commercial space: “In Australia”, he says, “our law does not recognise the difference between commercial and private space [yet] so much of our space is … in control of private enterprise.” He identifies this as an international issue where courts in the US are seeking to define “quasi-public spaces.”

Broadly then, urban public space can be understood as having architectural, geographic, social and economic dimensions. All of which, for the city-dweller, impact the layered material and memory residues of events, communal and personal and the way a city’s spaces and built environment are experienced.

Memory and the city

To focus at a personal level, the texture of a city allows specific memory places – places of personal meaning, freedom or pleasure – in which people may ‘locate’ or ‘identify’ themselves. Such places are markers for the passing of time, or serve as places for reflection, or of social contact.

Further, places of residual memory can be understood in two ways: the first concerns these personal sites of meaning and memory privately granted by their users, and second, as places configured as (designated) sites for communal meaning or official memory – identified by signifying architecture, proper names or exhortations that invite our complicity. Memory and meaning can also be alienated in over-aestheticised public space or by over-determined signifiers. Marc Augé calls this tendency produced by supermodernity … “non-places”, by which he means “spaces that are not themselves anthropological places and … do not integrate earlier places: instead … are listed, classified, promoted to the status of ‘places of memory’, and assigned a circumscribed and specific position”. These fabricated memory places dot the urban landscape and I include in these shopping malls, arcades and super stores.

As cities are rebuilt the newly built parts, by removing the material remains and practices of the past, obliterate or rewrite memory and are in their newness removed from time. But, how this is done is crucially important. Cities are inevitably mutable; are always in flux. As such, the spaces between specific places and structures – existing or newly created – unlike non-places, exist in the temporal world of change and action. The future city, through physical transformation, erases memories or, significantly, creates new opportunities for memory. These new places, in their design, function and approach may restrict freedoms or enhance possible experiences. For many cities in Europe the erasure of the particularities of place was realised instantaneously and traumatically and the re-establishment of these cities has included a process of reflection on the nature of each city. The result of this is particularly evident in Berlin.

New places

Optimistically, as cites are renewed, developed, or expanded there is the possibility for new evocative places to be created – squares, parks, passageways, streets, buildings and objects – that define space. New opportunities for human interaction and movement can enhance the experience of the city. What are the qualities that would allow for such enhancement? The answer I propose is in the contrast between those urban places that privilege human action, places that are relational over the spectacular and controlling spaces of, say, Haussmann’s Paris, Speer’s Berlin or new Beijing. These cities have been designed to aid modern commerce and treat the population as an undifferentiated mass.

Apart from the particularities of places of a particular scale and character, the ‘places’ to which we choose to form our attachments include general districts, vistas and skylines and thus may include the shape of the city itself as spectacle. Consequently, to look at the city at ground level or from a distance is to see it revealed in distinct ways. To the pedestrian, whether interesting or offensive, the city is a labyrinth of pathways and destinations; in its complexity it provides glimpses or blocks our view; it is stimulating or tiresome. As a panorama, its mass provides a skyline, the image of ‘city’; seen from the outside or from a privileged high vantage point, it is pure visuality. The distanced experience rejoices in mutability itself. (fig.3)

fig.3 Richard Dunn, Stadt 3 2005 colour photo 30x81cm (© author)

As in the cinema, we marvel at the way new images of the city, as idea, are endlessly presented to us. Guy Debord offers us a measure of the transitional distance from alienated public space at street level to the spectacular image of skyline in proposing that “(t)he only interesting undertaking is the liberation of everyday life”, adding in terms that continue my cinematic analogy, that “(t)his entails the withering of alienated forms of communication.”

Public spaces, everyday life and between

It can be argued that new urban ‘public’ spaces such as art museums and sports arenas, ceremonial or gathering places, justified by their potential mass appeal, have themselves become places of spectacle and alienation of the individual within the mass. Melbourne’s Federation Square is a good example of the success of such places. In developing major public projects, governments are anxious to demonstrate their management credentials in addition to their traditional political role as social regulators. Governments have increasingly marginalised public ownership of public space on the assumption that all ‘space’ as property is an asset to be managed or is a container for an activity to be controlled.

The effect of 9/11 on the regulation of public space has added a further dimension in levels of surveillance and control. As non-spaces have increasingly become a feature of our cities, the left over, free or ‘between’ spaces have largely disappeared. However, the everyday life of the city is not only a matter of a particular function or economic benefit, although these are the factors that dominate its architecture and planning, but of haphazard use. And, like art, the use of a city is not necessarily determined by ‘usefulness’ commonly understood. Perhaps one can say that ‘everyday life’ itself – like ‘ordinary people’ – is now a term loaded with functional and economic values, a political term indicating the daily struggles at the margins of the economy and affecting the election of governments and a rich seam to be mined rather than a zone of personal freedoms and joys. This last point is addressed to the relationship between the layout, facilities and infrastructure of cities and the quality of life.

Cities

At this point, it is necessary to identify what is the idea of ‘city’ being inferred by the discussion of its spaces. ‘City’ can imply a certain density of buildings and spaces (common in Europe) or like Brisbane, be simply geographical. The ‘city’ in an Australian or American context necessarily includes the suburbs that spread from dense high-rise centres. Although there may also be other ‘centres’, such separated agglomerations of distributed CBDs create a nascent megalopolis rather than a truly multi-centred or networked city. Suburbs, with setback detached houses and yards, their shopping strips and malls, are at a macro level themselves ‘between zones’ in a metropolis just as the streets, parks, intersections and squares are between zones in a city’s central business area. In the car-dominated suburb, the public experience of public space is largely restricted to the footpath and nature strip (visually leaking into front yards and so on), the shopping plaza, the parking lot, and to a more limited extent, parks and sports fields. The rest of the ‘public zone’ is the spectacle of changing views from the car and is temporal in nature. Consequently the quality of response to public space in different cities will depend on opportunities embedded in their different structures. It is in the interstices of cities – the between zones – that opportunities for imaginative use are presented. Perhaps all interesting imaginative architecture or art in public space is at least metaphorically in the between.

Deconstruction and the between

I want now to take a detour into denser territory – that of deconstruction in architecture and the theoretical underpinning of betweenness. Jacques Derrida introduces this idea in The secret art of Antonin Artaud. Here he articulates a zone between the support and the surface, where the subjectile (the material support of a painting or a text) is defined as that which ‘has no consistency apart from that of the between.’ As Julian Wolfreys observes of Derrida:

The subjectile is both ‘a substance, (and) a subject’, which as Derrida tells us ‘belongs to the code of painting and designates what is in some way below (subjectum)’, occupying a liminal place or, more accurately, a taking place, a becoming of the between, which it both is and is not: ‘between the beneath and the above’ says Derrida, ‘it is at once a support and a surface … everything is distinct from form, as well as from meaning and representation …’.

In this sense the subjectile is, in Wolfreys’ understanding, a term that “marks and remarks a certain crossing of borders, instituting the very borders that it crosses, while having ‘no consistency apart from that of the between’.” What does this have to do with a discussion of urban space? Specifically, the idea of betweenness drawn from Derrida has informed architectural theory and is evident in its practice since the nineties. But it is the implication of action, of mutability, unfixed or unresolvable, that is most interesting in this conception of the between as “a taking place”’ or as he says, “a becoming”; it is the active, temporal implication of his idea of the subjectile, which is so suggestive, where “between” becomes a verb.

Remaining for a time in the realm of deconstruction in architecture allows a clear distinction between theory-driven practice and architecture as a site of action. The Derridian ‘between’ is most apparent in the work of a number of architects whose practice was initially theoretical: Bernard Tschumi in Parc de la Villette in Paris and Le Fresnoy; Peter Eisenman in his Wexner Center for the Visual Arts and the Aronoff Center for Design and Art (both in Ohio) and it is manifested in the grid rotations and superimpositions of the his early ‘House’ concepts.

Staying with Eisenman: he has identified four key elements as necessary to displace traditional approaches to architecture. Along with ‘absence’, the ‘uncanny’ and ‘two-ness’ is ‘betweenness’. This is described as “something which is almost this, or almost that, but not quite either”, echoing the Derridian subjectile as that which “is and is not”. Eisenman’s idea of betweenness is precisely to avoid dualism (or ‘two-ness’) and establishes a zone of uncertainty.

By example, in Eisenman’s Wexner Center (1989), betweenness was conceptually referenced in the non-alignment of different abstract representations of space – the misaligned ‘grids’ of the city of Columbus and the campus of Ohio State University. This disjuncture is expressed in a three dimensional grid inserted into the building, reminiscent of Frederick Kiesler’s 1925 ‘City in Space’. Together with this abstract idea is an archaeological reference or reconstructed memory device in the form of a fragmented rebuilding of the demolished university armoury as office space. These conceptual subtleties may be no more overt in this project than the similar strategies employed by Bernard Tschumi, or by Daniel Libeskind, in his Jewish Museum Berlin. Libeskind incidentally calls this building “Between the Lines”. Emphasising the didactic nature of the project. On his website he says, “I call it this because it is a project about two lines of thinking, organization and relationship … a straight line, but broken into many fragments … [and] a tortuous line … continuing indefinitely”,

Eisenman in the Wexner Center creates a further disjunction between the way the building can be used and its expected functionality. He challenges expectations of the building’s meaning by creating friction between art and its architectural container. The building is designed so that it would specifically challenge artists’ expectation of neutral exhibition space for their use – the white cube, The arts centre created “for avant-garde and experimental arts” is intended to be difficult for artists The architectural projects to which I have so far referred operate like ‘texts’ or propositions rather than material ‘places’ to be experienced or interrogated or reinterpreted in their use.

Space and place

But this question of architectural functionality as a principle of modernism is, in another way, fundamental to the human use of public space, about who decides architectural meaning and how meaning is conveyed. Marc Augé, in distinguishing between ‘place’ and ‘space’ marks this kind of difference: “If a place can be described as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place”. In underscoring the effect of action and time on place and space (in a seeming reversal of Augé’s prescription, but incidentally capturing the active component of Derrida’s ‘between’), Michel de Certeau says, “space is a practiced place.” “Thus”, he continues “the street geometrically defined by urban planning is transformed into space by walkers.” At the basis of such a remark is the degree to which architecture provides space for free (democratic) human action and interpretation as opposed to expecting a particular response, or acquiescence.

Such flexible places are decreasingly seen. There are few leftover spaces that invite unprogrammed action and few new spaces are intended in this way. Yet, in an echo of Guy Debord, it is in the interstices that “socially vital life” is possible. Martin Buber writing in 1938 articulates the richness of the space between as a situational space rather than a gap between opposing tendencies. “Between”, he says, “is not an auxiliary construction, but the bearer of what happens between men; it has received no specific attention”, he continues, “because … it does not exhibit a smooth continuity, but is ever and again re-constituted in accordance with men’s meetings with one another.”

Big projects for, or in, public space are thought of by their authors as endpoints, as destinations, contained finalities. Yet the process of exploration and discovery is as interesting as the point of arrival. The implication of Buber and Debord’s thinking for architecture is to shift the emphasis to process, and process is unthinkable without putting to the fore the unpredictable human uses of public space.

The street

Flowing from these ideas of the between that precede those of Derrida and Eisenman, and drawing on the concepts of situation and play in a humanist framework, other architectural solutions have been possible. In 1953 Peter and Alison Smithson claimed that “the idea of the ‘street’ is forgotten” and with it “the creation of effective group spaces”. Recognising such situational aspects of public space for the individual, Jeff Malpas, recently interviewed by Alan Saunders on ABC radio’s By Design program, commented that we are shaped by and shape places in the city – space for reflection, place for solitude – “we look for such spaces” he said, “if they aren’t provided.” “We are thinking remembering creatures only in relation to place – and place can be social or for solitude.” For the artist Vito Acconci, “A public space is occupied by private bodies. These private bodies have hidden feelings, and private lives, and secret dreams.”

The street was the crucial social element of the city where unplanned interactions could take place between communal users of public space. In this sense the ‘street’, and similar conduits for movement, was the space between those areas for designated, already determined purposes (seen in the past as service zones). Looking at the present, is there space that is for contemplation, that is more personal or intimate or space that facilitates social contact? Do these needs have new currency? In terms of the public use of space, the ‘street’ as a conduit has main currents, eddies and side streams. It penetrates parks, enters buildings through their ‘public’ areas – forecourts, foyers, lifts and corridors. But to return to the street proper and the ambiguities of its function as the primary public zone, its liminality is still characterized by ambiguity, openness, and indeterminacy, and it is to this that architectural history and practice may turn.

Aldo van Eyck’s focus on the street to create 734 playgrounds in post-war Amsterdam is no surprise. Taking advantage of the left over or ignored bits of a city; its street intersections, roundabouts, spaces between buildings, and so on, van Eyck gave them new social functions. As detailed in Lianné Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis’s book on van Eyck, Humanist Rebel, the decision to make playgrounds not parks, was to make places of interaction, usually in streets. Perhaps appropriate to the bleak immediate post-war years these playgrounds still contain useful models for urban development. These playgrounds became a distributed network in the city and, conceptually the model for a multi-centred city. In microcosm this approach is evident also in van Eyck’s Municipal Orphanage (1954), and Hubertus, a home for single parents, built in the mid-70s. Van Eyck responds to Martin Buber’s idea of das Zwischen, (which he translates as “the inbetween”), drawn from Buber’s major work Ich und Du (1923), in locating urban places for dialogue and action. Van Eyck’s architectural approach, and that of his Team Ten colleagues, was on process rather than product, focussing on circulation and meeting points. The production of architectural and urban space, in his thinking, serves a community, not function itself, – at a cognitive level, and in time. Buber’s notion of a meeting between ‘I and you’ is relational, a personal event in space, holding a complexity of meanings, responses and understandings. Here is van Eyck’s comment on place and space: “Places remembered and places anticipated dovetail in the temporal space of the present. Memory and anticipation, in fact, constitute the real perspective of space; give it depth.”

The Smithson’s network-like Cluster City (1952-53) and extensions to the University of Bath (1978-88) were also alternative models to rational planning. Peter Smithson says of the Bath project that it was “an attempt, in a more complex way, to connect the lives of people, the life of the services, and the life of the fabric together”

This focus on city-dwellers as a community of individuals is at odds with the strict, mass-directed functionalism that dominated the post-war period. European rebuilding and pre-war modernist urban planning in both Western and Eastern Europe tended to the large-scale solution, so evident in the project in Chemnitz. ‘Team Ten’ (including van Eyck, Peter and Alison Smithson, John Voelker and Shadrach Woods), was the European younger generation who challenged rigid functionalism at the 1956 CIAM X (International Congress of Modern Architecture). Their new approach to planning had much in common with Situationist International (SI – Debord, Asger Jorn, Constant). The present situation is superficially very different from the circumstances of fifty years ago, but in a period of individual landmark buildings, with an emphasis on image – ‘the building as logo’ – a humanist approach to architecture and planning still has currency.

Art and architecture

I have suggested that art can play a role in a new realisation of public space at a conceptual level rather than as adornment. It is worth looking at this firstly from an historical perspective. It may seem curious that van Eyck’s design for the playgrounds used simple geometric forms for the layout of sandpits or the structure of climbing mountains and frames given his humanist intentions. But these forms have their genesis in his knowledge of pre-war Dutch Modernism, and particularly of Theo van Doesburg and his role in De Stijl, post-cubist architecture as a plastic art. Urbanism became the subject of the work and thinking of the Cobra group and Situationist International Debord, Asger Jorn and Constant.

Given that most of my references are to ideas generated between 1950 and the mid-eighties, the question must be asked whether the present circumstances of accelerated and embedded alienation now lend themselves to solutions evolving from this time?

Vito Acconci – literary theorist, poet, and performance artist – has worked in the field of architecture since 1980s as Acconci Studio, usually on small-scale projects, building and open space revisions and enhancements. Acconci’s career has focussed on the boundaries between the private and the public and therefore the social context is a predominant theme. Also in space outside architecture, but nevertheless in the between space of “the interhuman sphere: relationships between people, communities, individuals, groups, social networks, interactivity, and so on”, is the work of a number of artists – Pierre Huyghe, Maurizio Cattelan, Gabriel Orozco, Liam Gillick, and others. There are, of course, many examples to give in art and architecture, but my point is more on a conceptual level.

There are current assumptions perhaps that the Internet is the new street, and as a virtual medium for information access, communication and alienated interaction it is without parallel. The Internet makes it easier to access ideas and people as information. Clearly, the street, ‘stoop’, café, or pub no longer have the social importance they once so essentially held. But Big Brother and the architectural fabric of our cities notwithstanding, we still live in a world of actual relationships in real space and the question that I have raised can be most actively addressed through more engaged response in the planning of our public spaces and the visual field.

This paper questions how public space is treated, and also how the public itself is accommodated in urban planning. The kind of flexibility I am advocating in situation- and humanist-oriented architecture and planning has a trajectory from de Stijl to Team 10, and – after the influence of Dada/Surrealism – Cobra, Situationist International to Cedric Price and Archigram to the present. So I am not proposing a style but an approach at a micro and macro scale to planning that is more responsive to the social needs and purpose of cities. Although this tendency is not so clear in the present architectural thinking, given the dominance of spectacle, didacticism and commodification. The challenge to the present fragmented approach to planning may be assisted by reconceptualizing planning and architecture that is more open to ideas from outside these disciplines including as practice, art, and speculative thinking including anthropology and archaeology.